There is a close interaction between people and places they inhabit. In the same way that a building’s energy may be affected by the ch’i of its inhabitants so too do buildings affect the people who use them.

In Cambodia, the Khmers designed architectural wonders using their knowledge of ch’i to produce monuments of power that extended far beyond today’s conventional concepts. Integrating myth and sculpture they created many temples, royal cities and palaces. Even their reservoirs and irrigation systems used the delivery of water to create a powerful flow of ch’i.

The flow of life

The agriculture of the Mekong region is affected by seasonal rains. During the spring melt and the monsoon season, the flow of the Mekong River is so great that it reverses the flow of the river Tonle Sap, and pushes water up into the Great Lake in the central basin of Cambodia. From a shallow, muddy chain of pools it is transformed into a huge lake, 80-100 miles long, 15-30 miles wide and 40-50 feet deep in some places. As the waters receded, they left millions of fish stranded in the muddy pools.

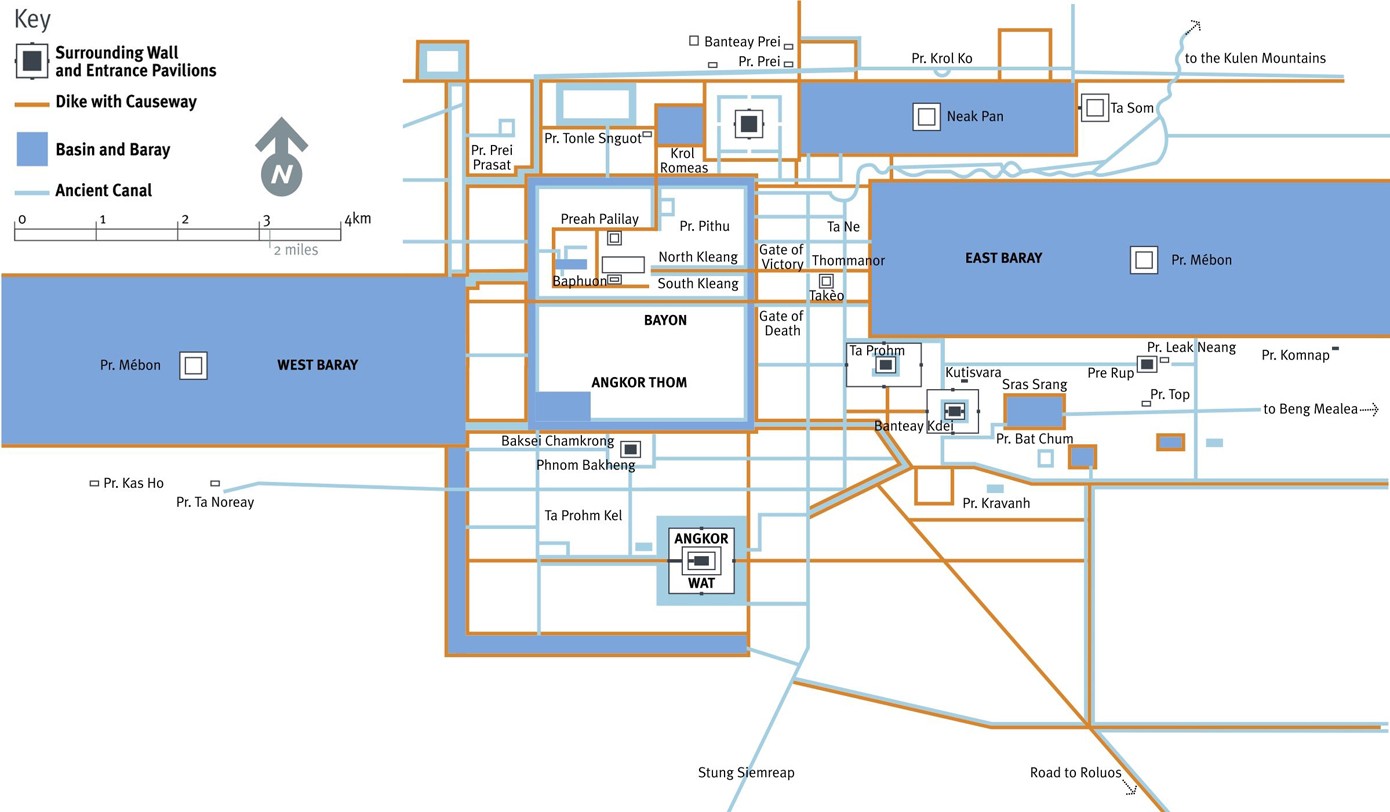

To prevent their fields from drying out in the dry season, the Khmers devised a system of sophisticated reservoirs and irrigation canals to distribute the stored water as well as providing transport routes. It was one of the primary roles of the king to develop and maintain this system and ensure his country’s continuing prosperity. In the capital, Angkor, the temple complex known as Angkor Wat was centred on a radiating system of canals which dwarfed the monuments and shrines and created a living system of energy. This system of ch’i distribution was central to Khmer culture.

SPONSORED

The sacred traditions in India are well known for using yantras, geometric sculptural

compositions to focus a person’s mind. And looking at the complex ‘ch’i-irrigation’ system of the temples, sculptures, causeways and canals, Angkor could be viewed as a giant yantra.

Imagery and symbolism

Khmer temples and waterworks were laid out so that the temples and royal city represented the central Mount Mandara while the gods, demons, and snakes formed giant balustrades for the causeways. Meanwhile, the reservoirs and canals distributed the water charged with ch’i to the outlying fields. As such the Khmers succeeded in creating a powerful symbolic

representation of their spiritual beliefs.

Above Note the extensive waterways

Above Note the extensive waterways

“The Khmers united yin and yang feng shui in one continuous structure”

The Khmers believed that after death their kings were merely transported to ‘the other side’ and were still able to remain in touch with and help their descendants and subjects. In the similar way to the Chinese practice of locating tombs at sites with good ch’i, the Khmers made their mortuary temples a part of their ‘ch’i irrigation’ system.

The tombs took on a significant meaning for everyday life. Keeping in touch with former rulers on the ‘other side’ and tapping into their wisdom formed an integral part of society. Funerary temples and sculptures were not just an egotistical attempt to better a ruler’s afterlife.

Hidden glimpses

When you approach a doorway into a Khmer temple an abrupt and sharp transition occurs, almost like a knife cut. The molding bands at the base of the wall end abruptly, although they normally curve around corners. Similarly, the pilaster capitals and the ornamental entablature over the top of the opening are abruptly sliced off on the side of the opening, while on the opening there is almost invariably a second surround of pilaster and entablature, far more richly and finely ornamented.

This abrupt division also occurs on the terracing and stairways to these doorways. The sculptural surfaces are rent apart, with the steps almost always recessed behind the surface of the terraces. These two devices give the impression of the surface of the temple being cut through and slid apart, revealing a glimpse of an inner temple.

Sculptural details

Atop the central Bayon temple and the gateways are giant sculptured faces of the king facing in the four compass directions. While they are often described as the faces of ‘Big Brother’ watching every movement of his subjects, in fact their eyes are closed in meditation, as in most Khmer sculpture.

The breath of life is a dominant sculptural feature of Angkor. Head-dresses often represent the ‘flame emanations of aura energy’ while hooded cobra head-dresses project the serpent image.

All over the temples are fine-grained banded profiles and layers of ornament. In particular, when looked at with the ‘soft eyes’ of meditation you get the feeling of slow-motion emergence.

What the Khmers had created at Angkor was a framework that enfolded and transformed their whole kingdom. No matter where you were, on roadways, canals, in fields, towns, or between temples and reservoirs you were part of a system representing the world of subtle energies.

|  |  |

![]()

SPONSORED